Seemingly lost in the confluence of recent news, whether those that are covering North Korea’s intransigence, Mueller’s investigation, or #memogate, is more substantive debate on how the administration’s “Tax Cut and Jobs Act” will now treat ongoing energy subsidies.

Will the new administration now reduce support of subsidies for renewables in favor of say coal? If so, by how much and what message will this now be sending to the science advocacy that supports the view that climate change is real? What real costs are not being calculated into business rationales for continued subsidies of energy sources? What are the trade-offs?

“No longer is there a trade-off between what you believe in and what you can make money off of,” Nancy Pfund, who co-runs DBL Partners, early investors in Tesla, and said in the New York times this time last year, weeks before the new U.S. administration’s inauguration.

Why This MattersHistory of Energy Subsidies

U.S. government subsidies for energy is as old as the nation, says Ms. Pfund in her seminal report “What Would Jefferson Do?” on how subsidies, a form of taxpayer-funded government incentive, have played a major role in meeting the energy needs of the world’s second biggest energy consumer (China is the first).

The report traced energy subsidies and tax credits (or levies) to as far back as 1789, when leaders of the new nation slapped a tariff on the sale of British coal that slipped into U.S. ports in ship ballasts.

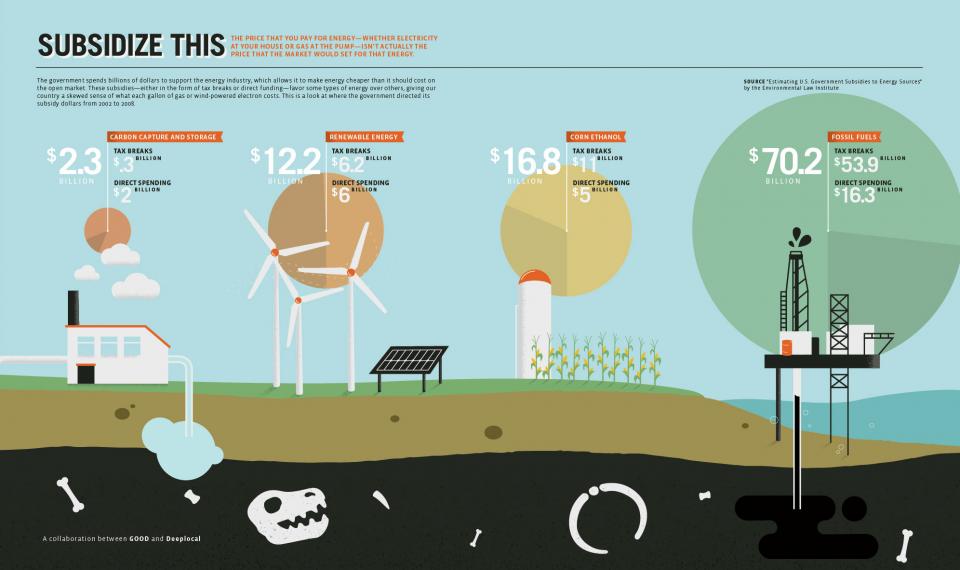

Significantly, the report also cited how subsidies for renewables have paled in comparison to those of fossil fuels.

Today, despite the progress made by the Obama administration, nearly $5 billion continues to subsidize the fossil fuel industry. Estimates by other analyses such as by Oil Change International say the subsidies might actually be higher, to the tune of $20 billion, if certain computations for tax credits or allowances are factored in.

Opposing analysis, such as by the Institute of Energy Research, an entity with known ties to the Koch brothers, suggest the higher subsidy numbers are overstated, arguing such computations outside of the U.S. system’s tax code should not be factored in.

However, what seems to be lost in the analyses are the real costs, or impacts, that those subsidies continue to make, and ultimately, taxpayers continue to indirectly fund. Those are nowhere in the current tax code. Should those costs be factored in at all?

Real Costs of Energy Subsidies

It’s been a few months since the autumn fires in California yet many outside of wine-country Sonoma or the Bay area seems to have forgotten. The fires caused nearly $12 billion in damage. Shouldn’t this cost be factored in as well?

Extreme heat that perenially now floods Pakistan costs the country by as much as $9 billion, according to some estimates. Shouldn’t this cost be factored in as well?

“The biggest climate threat facing Pakistan today is national security – the possibility of climate change and environmental factors destabilizing Karachi,” Sualiha Nazar an expert in Foreign Policy says.

Hurricane Maria cost Puerto Rico $45 billion to $95 billion in damage just two months ago, according to some estimates. Shouldn’t this cost be also factored in?

Alcen Renewable CEO Tao Kong put it best when he said price comparisons don’t take into account one of the most basic concepts in economics, which is externalities.

“Fossil fuel energy imposes real costs on society that are not priced into the cost of the fuel – the costs of pollution, air quality or of climate change,” Kong adds, “and is already making parts of the planet uninhabitable.” Parts of Puerto Rico, as of this writing, still remain without power.

What’s Needed – Real Debate, More Tools

Over five years ago, G20 nations called into question what role fossil fuel subsidies ought to continue playing to fund old energy projects.

Many called for its retirement then, saying that not doing so encourages investors to put resources into the fuels that are driving climate change, an assertion that is true. Globally, subsidies that support fossil fuels as energy sources surpass $600 billion, and dwarfs the $90 billion spent on renewables.

And so, as with the recent launch of a Tesla into a Falcon Heavy’s orbit by SpaceX last week, perhaps continued debate, visible action, and purposeful investment now remain in the hands of private markets.

SpaceX, as was Tesla, were in part funded by subsidies, so arguably, subsidies can still work to fund projects that benefit the social good.

What might be needed are systems to price in say, credible carbon price signals, as the innovative blockchain-based peer-to-peer carbon trading platform CarbonX is trying to do, along with more specific numbers on the costs or negative incentives, or impact created by fossil-fuel subsidies.

This way, the markets – pensions, institutional investors and perhaps even retail investors – will have better tools to decide, and act.

Read Some More

“Long History of Energy Subsidies,” Chemical and Engineering News, December 2011.

“Dirty Energy Dominance,” Oil Change International, October 2017.

“Vox and OCI Miscontrue Subsidy Landscape,” Institute for Energy Research, October 2017.

“Meet the 28-year old who is Building Utility-scale Renewable Energy Projects,” Medium, May 2017.

“Federal Support for Developing, Producing, and Using Fuel Energy Sources,” CBO, March 2017.

“What Would Jefferson Do?” DBL Investors, September 2017.

“Why We Need to Abolish Fuel Subsidies,” WEF, November 2014.

“Can Personal Carbon Trading Take Off on the Blockchain?” Fast Company, October 2017.